History

On August 1st in 1838, after centuries of revolt and resistance by enslaved Africans, Britain terminated “apprenticeship” in its Caribbean colonies, finally ending chattel slavery there. That historic event triggered the commemoration we witness today at the Lidj Yasu Omowale Emancipation Village, and throughout Trinidad & Tobago. The first celebration of emancipation in 1838, was a solemn one. On the occasion, ex-enslaved Africans made their way to centres of worship in the towns and returned to the country by early afternoon. The Port of Spain Gazette reported that, ‘order and quiet reigned’, and the day passed ‘without excitement of any kind’. However from the next year, 1839, Emancipation was celebrated with pomp and ceremony.

An Unofficial Holiday

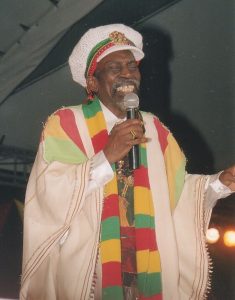

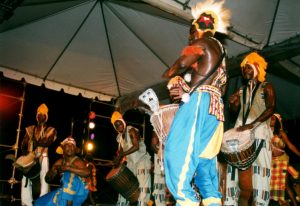

Such celebrations took many forms. The most organized celebrations could go on for several days. There were processions, church services, speeches, thanksgivings, and fete’s which included drumming and dancing. The day was often marked by sporting events such as cricket matches. Even in areas where they organised no formal celebrations, Africans stayed away from work on Emancipation Day and spent the day with family and friends forcing businesses to close. The formerly enslaved took ownership of Emancipation Day despite the refusal of the colonial government to officially declare a holiday. 2 “Columbus made me a Trinidadian; God made me an Afrikan” Elma Francois Pan-African Concert July 31, 2014. Multiple grammy award winner, Angelique Kidjo, performing to a packed audience at the Lidj Yasu Omowale Emancipation Village, Queens’s Park Savannah. An excellent example of an early commemoration of emancipation is provided from a description of the celebration in Carenage, through the journal of a Catholic Priest. “On any given August 1st , the people started the day with a Catholic mass, which was followed by drumming, singing, dancing and a procession. This celebration continued with the same intensity and exuberance for three days, after August 1 st .” There is a description of how in 1882, the African organizers from this village built a bamboo edifice for the celebration. They collected funds, bought food and drink, issued invitations and after the customary mass was said, engaged in their festivities.

“Columbus made me a Trinidadian; God made me an Afrikan”

Elma Francois - Pan-African Concert - July 31, 2014.

1888 The Jubilee

The 50th anniversary of the celebration of emancipation in 1888 (the Jubilee), grand in its scale and dispersion, received wide media coverage, in part driven by controversies raised by high-profile middle class participants, whose demands included an official holiday. Outside of Port of Spain there were reports of elaborate celebrations in San Fernando, Arima, Arouca, Chatham, Couva, California, Mayaro, and Tortuga. The jubilee celebration in the capital continued until the next morning. In the evening time there were private and public dinners, a fireworks display on Chacon street and a dance at Princess Elizabeth’s grounds.

Celebration of “Discovery” substituted for celebration of Freedom

In the 1920’s, with the support of prominent locals, the colonial authorities proclaimed that August 1 would be observed as Discovery Day. Despite the offi cial pronouncement, commemorations of emancipation continued. A prominent celebration was that organised by the NWSCA (Negro Welfare Social and Cultural Association (called the Negro Welfare Association), founded by Elma Francois and later led by Jim Barrette and Christina King. In the 1930’s they adapted their celebration to commemorate Discovery Day along with Emancipation Day, fighting to ensure the preservation of this sacred memory against the overwhelming official and media focus on Columbus. But by the end of the 1950’s the emancipation commemoration had declined considerably. Significantly however it was kept alive in small pockets by some elders who felt deeply committed to this sacred memory. A few nationally prominent stalwarts like George Weekes consistently advocated its revival. This was eventually accomplished by the National Joint Action Committee in the early 1970’s.

Revival

Popular celebrations organized by NJAC in different parts of the country and energized by the transformative messages of Black Power marked the national revival of the emancipation commemoration. These rallies were supplemented by community celebrations, many of them organized by member groups of NJAC. In the 1980’s John Cupid introduced a street parade in Point Fortin. Lancelot Layne made a mark on the celebrations by organizing a flambeau light procession in Arouca and a street parade in Port of Spain. TANA (the Traditional African National Association), led by a former NJAC Executive member, Lidj Yasu Omowale, first organized celebrations at the Queens Park Savannah, opposite White Hall, then moved to Woodford Square and the POS Town Hall. With the growing popularity of these events and advocacy by groups and individuals, Prime Minister George Chambers, on the 150th anniversary of the Proclamation of Emancipation in 1984, declared that August 1st would be a holiday, Emancipation Day, from 1985.

Birth of the Emancipation Support Committee

As 1992 approached there was a high profile international thrust to focus global energies on quincentennial celebrations for Columbus. The Emancipation Support Committee, with Lidj Yasu Omowale and Khafra Kambon as co-chairs, was formed as an umbrella body, to strengthen the emancipation celebrations. This derailed efforts to re-impose the arrival of Columbus as the dominant motive for celebration on August 1.

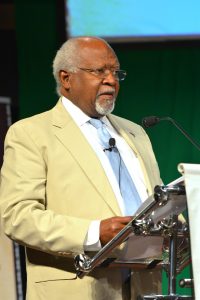

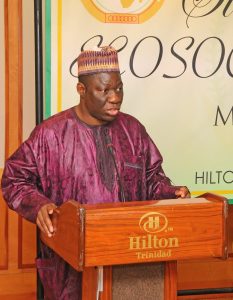

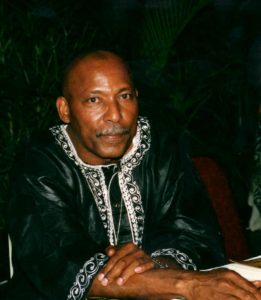

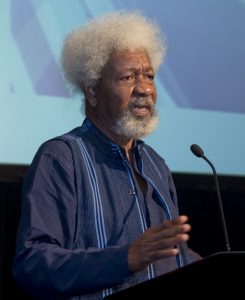

Honouring our Heroes and Elders

In much the same vein as honouring the struggles of our ancestors, recognizing those still in our midst whose work and unique talents uplift generations of African peoples everywhere is at the very heart of the Emancipation celebrations. Thus, the Spirit of Emancipation Award and the Henry Sylvestre Williams Award of Excellence have over the years been given to individuals who have distinguished themselves by their contributions and service to their communities. Just as Henry Sylvestre Williams was himself a noted pioneer and leader of the pan-African movement, notable recipients over the years have included world leaders including Presidents of Senegal and Nigeria, academics, scientists, artists and entertainers.